Dive into the Power & Passion of ‘Tenor Madness

In the vast panorama of jazz, Sonny Rollins’ “Tenor…

In the aftermath of Charlie Parker’s death, jazz, that great river of American sound, seemed to flow with a tinge of melancholy. And so, last night, I immersed myself in Sonny Rollins‘ “Rollins Plays for Bird,” a complex tribute to the late genius, a jazz titan paying homage to another.

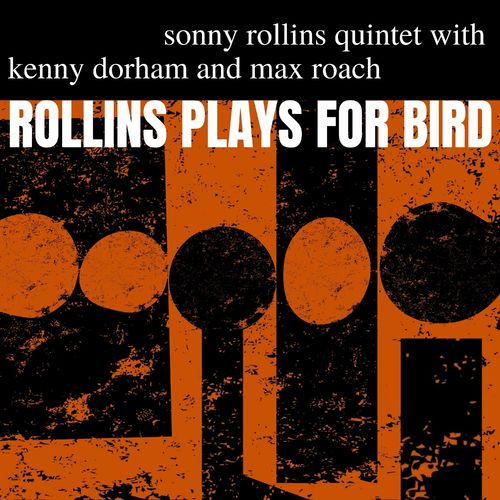

The year was 1957, and Prestige Records had brought together a quintet of prodigious musicians. There, in the womb of a New York City recording studio, a sonic monument was conceived. It was no ordinary tribute; the album stood as an affirmation of Parker’s lasting impact on the world of jazz.

In the months leading up to the session, Rollins had been traversing uncharted territories of saxophone virtuosity, his talents expanding like the universe itself. Kenny Dorham, the trumpeter, had been refining his unique voice, while the rhythm section—Wade Legge on piano, George Morrow on bass, and Max Roach on drums—laid the groundwork for their towering improvisations.

These musicians, each a disciple of Parker’s gospel, poured their souls into the music, fusing their talents to create a tribute that was as timeless as it was heartrending. And within their performances, the spirit of Parker soared, his influence saturating every note and phrase.

As I listened, the album’s opening salvo—a medley of tunes indelibly linked to Parker—held me captive. Rollins’ tenor saxophone danced through the melodies, his tone golden and assertive, while Dorham’s trumpet responded with an aching lyricism. Legge, Morrow, and Roach coalesced, forming an undercurrent from which the horns rose, triumphant and unbound.

This medley, a kaleidoscope of emotion, traversed the vast landscape of Parker’s repertoire, culminating in a stunning rendition of “Star Eyes.” The tune, a beacon of light in the darkness, brought the quintet together in a masterful display of unity and virtuosity.

Yet it was “Kids Know,” an original composition by Rollins, that struck me deepest. The piece, set to a lilting 3/4 rhythm, served as a playground for the musicians, who took turns exploring its harmonic depths. Rollins wove a tapestry of intricate melodic lines, while Dorham’s trumpet shone with vibrancy, his phrases nostalgic and visionary in equal measure.

The rhythm section—Legge, Morrow, and Roach—proved indispensable, their contributions elevating the music to new heights. As the piece unfolded, the quintet navigated the labyrinthine structure with dexterity and grace, each musician a vital thread in the fabric of the performance.

In the tender ballad “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face,” Rollins’ saxophone, rich and emotive, took center stage, while Legge’s sensitive piano accompaniment served as a whisper of support. And finally, “The House I Live In” brought the album to a close, a powerful reminder of the unity and camaraderie shared by these musicians, bound together by their love for Parker and his music.

Throughout the album, one can hear the echoes of bebop and hard bop, the musical languages that defined Parker’s career. The tunes, charged with introspection and raw emotion, offered a window into the world that Parker inhabited—a world of dizzying complexity and unfathomable beauty.

Upon its release, “Rollins Plays for Bird” was met with critical acclaim, hailed as a fitting tribute to the man who had redefined the very essence of jazz. As the years have passed, the album’s significance has grown, its place in the annals of jazz history firmly cemented.

Listening to “Rollins Plays for Bird,” I was struck by the musicians’ ability to transcend the temporal and spatial boundaries that separate them from Parker. Through their artistry, they conjured his spirit, honoring his legacy while simultaneously forging their own path.

The album serves as a testament to the power of music, its capacity to communicate that which is ineffable, to bridge the gap between life and death, and to pay homage to those who have shaped the course of history. In their tribute, Rollins and his compatriots remind us of the profound debt we owe to the pioneers who came before us and the responsibility we bear to carry on their work.

As I emerged from my reverie, I felt a renewed sense of purpose and an invigorated appreciation for the jazz tradition. The music of “Rollins Plays for Bird” had transported me to a realm where the past and present collided, where the echoes of Charlie Parker’s genius reverberated through the performances of his disciples.

And so, with a heart brimming with gratitude and an ear attuned to the music of the spheres, I shall continue my journey through the world of jazz. For I know that the spirit of Charlie Parker lives on in each note, in each phrase, and in each of the countless tributes that celebrate his indelible mark on the history of music.